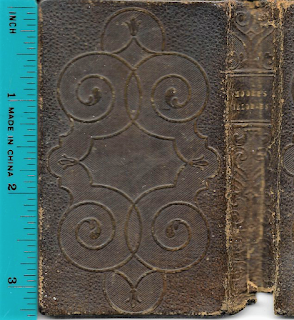

The most precious aspect of having this tiny (pocket-sized) booklet in my antique collection is that it belonged to my great-great grandmother Sarah Hewitt, an Irish immigrant to the rural Lambton County farming district of Sombra, ON, in about 1860.

Moore's father was a spirits grocer with an establishment on Grafton Street in Dublin. His mother devoted herself to her only son’s excellent education and encouraged him to avoid the rebellious element in the country that challenged British rule in Ireland. During that time “Catholics had no right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, to educate their children, to engage in most professions and to bear arms”. (De Ford, 1967)

During the years when Moore was a young man the opportunity appeared for Catholics to attend Trinity College, after his attendance at various grammar schools, and with enough savings in the family for the young lad to attend with a vision to practice law.

Two of Moore’s close friends and classmates at Trinity belonged to the “United Irishman” and participated in the unsuccessful uprising of 1798. Moore wrote an anonymous letter to the organization’s publication “The Press”, but was discouraged by his parents and avoided future participation. Trinity College began investigating some of the ideas that were being promulgated and debated and Moore was fortunate to be able to remain there as a student after certain reassurances.

Moore’s friends Robert Emmet and Edward Hudson remained involved but avoided involving Moore who was less suited. Ironically, it was Hudson who introduced Moore to the new Irish songs that were being discovered and Emmet who relished in them as possible marching tunes.

Ireland was hopeful in the spirit of the recent French Revolution, following that of the American Revolution, that freedom would finally blossom in the motherland. In the 1798 uprising, Robert Emmet was wounded, while Edward Hudson was imprisoned and exiled. Following the uprising in 1803 led by Robert Emmet, Emmet would be hanged and then beheaded.

Moore penned the song “Breath Not His Name” in his honor along with “She is far from the land” for Emmet’s sweetheart, Sarah Curren. Ironically it was his other friend Edward Hudson, a flutist, who introduced Moore to the new Irish songs that were being discovered. Moore writes about Emmet:

“Were I to number, indeed, the men among all I have known who appeared to me to combine in the greatest degree pure moral worth with intellectual power, I should, among the highest of the few, place Robert Emmet. Such in heart and mind, he was another of those devoted men who, with gifts that would have made them ornaments and supports of a well-regulated community, were yet driven to live the lives of conspirators and die the death of traitors by a system of government, which it would be difficult ever to think of with patience, did we not gather a hope from the present aspect of the whole civilized world that such a system of bigotry and misrule can never exist again.”

The beginning of the 19th century saw the rise of Romanticism, following the world’s moving away from the path of scientific deduction and mechanical exactitude in the 1780s period of “reason.” Now it was “feelings.” French philosopher Blaise Pascal noted, “The heart has its reasons, which reason knoweth not.” Chateaubriand called it the “centrality of the irrational.”

The popularity of the pianoforte with Moore, which replaced the harp in middle-class homes, began to be replaced by the six octave piano as Beethoven was composing for such an instrument before any piano existed, creating this new market.

Moore never liked the way his songs were published and disagreed with the manner that he wished them to be performed. In his notes, he suggested that one attend “as little as possible to the rhythm or the time in singing them. The time should always be made to wait for the feeling, words need to be as nearly spoken, the observance of time completely destroys all of those pauses.”

Moore was concerned about the mechanical nature of organized music, where the feeling was lost to the “unrelenting trammels of an orchestra”. Moore’s style was to play various chords with intermittent lyrics and spoken poetry.

In his book, The Birth of the Modern, Paul Johnson notes:

“But the public was enthusiastic, music was soon seen as the interpreter, the enhancer of poetry. A man like Thomas Moore quickly achieved a worldwide reputation as a great lyric poet precisely because he sang his songs in the drawing rooms of the great. Indeed, music came to be revered, increasingly, as a key to all of the arts.” (Johnson, 1991)

Moore’s melodies spread to the American continent and, upon Moore’s arriving in Philadelphia, discovered his music’s popularity.

Sarah Hewitt was the grand mother of my grandmother Louise Ruddick Wright and I inherited six Irish Anglican religious texts given to her as a young woman before coming to Canada with her daughter and son-in-law, James and Catherine Ruddick. Sarah's husband Frederick Hewitt (my great-great grandfather) passed away before the family left for Canada.

Louise Ruddick married my grandfather Wesley Wright in 1896. They maintained the Wright homestead in Dresden where both my father Kenneth and I were born.

I do not really know why, but the name Thomas Moore has haunted me recently to the point that I undertook some research to find a little more information on the life of this rather historic literary figure that had eluded me all these years.

And boy, was I ever surprised and duly impressed with what I discovered.

Thomas Moore (28 May 1779 – 25 February 1852) was an Irish writer, poet, and lyricist celebrated for his Irish Melodies published in about 1821. Their setting of English-language verse to old Irish tunes marked the transition in popular Irish culture from Irish to English.

Come to find out, Moore’s “Irish Melodies” were produced in both Dublin and London, as Moore began adding his poetry and lyrics to the lost Irish airs that were being discovered during various harp festivals and transcribed for piano by Edward Bunting. These festivals were organized by the retired physician, Dr. James MacDonnell, who also developed a reputation for developing various medical institutions, as well as a natural history museum in Ireland.

|

| Thomas Moore |

Moore's father was a spirits grocer with an establishment on Grafton Street in Dublin. His mother devoted herself to her only son’s excellent education and encouraged him to avoid the rebellious element in the country that challenged British rule in Ireland. During that time “Catholics had no right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, to educate their children, to engage in most professions and to bear arms”. (De Ford, 1967)

During the years when Moore was a young man the opportunity appeared for Catholics to attend Trinity College, after his attendance at various grammar schools, and with enough savings in the family for the young lad to attend with a vision to practice law.

Two of Moore’s close friends and classmates at Trinity belonged to the “United Irishman” and participated in the unsuccessful uprising of 1798. Moore wrote an anonymous letter to the organization’s publication “The Press”, but was discouraged by his parents and avoided future participation. Trinity College began investigating some of the ideas that were being promulgated and debated and Moore was fortunate to be able to remain there as a student after certain reassurances.

Moore’s friends Robert Emmet and Edward Hudson remained involved but avoided involving Moore who was less suited. Ironically, it was Hudson who introduced Moore to the new Irish songs that were being discovered and Emmet who relished in them as possible marching tunes.

Ireland was hopeful in the spirit of the recent French Revolution, following that of the American Revolution, that freedom would finally blossom in the motherland. In the 1798 uprising, Robert Emmet was wounded, while Edward Hudson was imprisoned and exiled. Following the uprising in 1803 led by Robert Emmet, Emmet would be hanged and then beheaded.

Moore penned the song “Breath Not His Name” in his honor along with “She is far from the land” for Emmet’s sweetheart, Sarah Curren. Ironically it was his other friend Edward Hudson, a flutist, who introduced Moore to the new Irish songs that were being discovered. Moore writes about Emmet:

“Were I to number, indeed, the men among all I have known who appeared to me to combine in the greatest degree pure moral worth with intellectual power, I should, among the highest of the few, place Robert Emmet. Such in heart and mind, he was another of those devoted men who, with gifts that would have made them ornaments and supports of a well-regulated community, were yet driven to live the lives of conspirators and die the death of traitors by a system of government, which it would be difficult ever to think of with patience, did we not gather a hope from the present aspect of the whole civilized world that such a system of bigotry and misrule can never exist again.”

An excellent scholar, Moore excelled in Latin, Italian, French, and particularly in Greek.

”His memory was prodigious and he could readily call to mind long passage from the Italian or French masters, as well as quote freely from the Latin and Greek classics (Mackay, 1951). Moore’s star began to rise when he did a translation of a Greek poet from the 5th century BC, “The Odes of Anacreon”, which focused on “wine, women and song” with the support of various English aristocrats. The sponsors came to appreciate his talent both in verse and the Irish melodies that he performed in the social circles of London.

Music was soon seen as the interpreter, the enhancer of poetry. A man like Thomas Moore quickly achieved a worldwide reputation as a great lyric poet precisely because he sang his songs in the drawing rooms of the great.

One account of Moore’s musical style was by Lady Blessington:

"We all sat around the piano, for one or two songs, he rambled over the keys awhile and sang, 'When first I met thee' with a pathos that beggars description. When the last word had faltered out, he rose, said ‘good night’, and was gone before a word was uttered. For a full minute after he had closed the door no one spoke. I could have wished myself to have dropped silently asleep where I sat, with the tears in my eyes and the softness upon my heart.”

”His memory was prodigious and he could readily call to mind long passage from the Italian or French masters, as well as quote freely from the Latin and Greek classics (Mackay, 1951). Moore’s star began to rise when he did a translation of a Greek poet from the 5th century BC, “The Odes of Anacreon”, which focused on “wine, women and song” with the support of various English aristocrats. The sponsors came to appreciate his talent both in verse and the Irish melodies that he performed in the social circles of London.

Music was soon seen as the interpreter, the enhancer of poetry. A man like Thomas Moore quickly achieved a worldwide reputation as a great lyric poet precisely because he sang his songs in the drawing rooms of the great.

One account of Moore’s musical style was by Lady Blessington:

"We all sat around the piano, for one or two songs, he rambled over the keys awhile and sang, 'When first I met thee' with a pathos that beggars description. When the last word had faltered out, he rose, said ‘good night’, and was gone before a word was uttered. For a full minute after he had closed the door no one spoke. I could have wished myself to have dropped silently asleep where I sat, with the tears in my eyes and the softness upon my heart.”

The beginning of the 19th century saw the rise of Romanticism, following the world’s moving away from the path of scientific deduction and mechanical exactitude in the 1780s period of “reason.” Now it was “feelings.” French philosopher Blaise Pascal noted, “The heart has its reasons, which reason knoweth not.” Chateaubriand called it the “centrality of the irrational.”

The popularity of the pianoforte with Moore, which replaced the harp in middle-class homes, began to be replaced by the six octave piano as Beethoven was composing for such an instrument before any piano existed, creating this new market.

Moore never liked the way his songs were published and disagreed with the manner that he wished them to be performed. In his notes, he suggested that one attend “as little as possible to the rhythm or the time in singing them. The time should always be made to wait for the feeling, words need to be as nearly spoken, the observance of time completely destroys all of those pauses.”

Moore was concerned about the mechanical nature of organized music, where the feeling was lost to the “unrelenting trammels of an orchestra”. Moore’s style was to play various chords with intermittent lyrics and spoken poetry.

In his book, The Birth of the Modern, Paul Johnson notes:

“But the public was enthusiastic, music was soon seen as the interpreter, the enhancer of poetry. A man like Thomas Moore quickly achieved a worldwide reputation as a great lyric poet precisely because he sang his songs in the drawing rooms of the great. Indeed, music came to be revered, increasingly, as a key to all of the arts.” (Johnson, 1991)

Moore’s melodies spread to the American continent and, upon Moore’s arriving in Philadelphia, discovered his music’s popularity.

He experienced culture shock visiting various locations in the new democracy and was most comfortable in Philadelphia, which mirrored the sophistication of his own urbane nature in London. Upon visiting Thomas Jefferson, he noticed that the President was dressed in “tweeds and Connemara stockings.” Moore’s music would become popular later from the American Civil War up until World War l.

|

This bronze statue of Thomas Moore stands on a traffic Island just to the north of Trinity College in Dublin. It was sculpted by Christopher Moore and unveiled in 1857. |

He would write the biography of the famous English poet, Lord Byron, after his death at his request, as they were good friends. There was universal appreciation of Moore’s poetic genius in that great poetic age, which produced Wordsworth, Scott, Shelly, Keats, and Byron. Mary Shelly, the author of “Frankenstein”, writing to Moore, refers to his “department of poetry, peculiarly your own song’s instinct with the intense principles of life and love”.

Edgar Allen Poe, the American poet, and author, is noted as recognizing his favorite song of Moore, “Come Rest in My Bosom”. For three-quarters of a century, more men and women read and loved Moore more than Keats, Shelly, or Wordsworth. Shelly was proud to acknowledge his own inferiority.

Despite this level of recognition, Moore would fall short in being recognized by the cultural leaders in Ireland. His success contrasted the life Edward Bunting was living and his publications were copied and reproduced by other publishers since no copyright laws existed until the late 19th century. Moore was able to capitalize on his airs and Bunting was uncomfortable with them being adjusted to suit his poetry.

At a gathering in Belfast, Bunting was honored and Moore was crushed that he was never mentioned, purposefully, being the possible poet laureate of Ireland.

“Ironically, when the Irish melodies did appear under another imprint -- the airs, of course, were public property-- Bunting, gracious if probably chagrined, said generously that they were “the most beautiful popular songs composed by any lyric poet.”

Moore’s five children would predecease him, three dying at a young age. In 1846 he would write, “The last of our five children is gone and we are left desolate and alone, not a single relative have I now left in the world”, his father deceased in 1825, and his mother in 1830, sister Ellen would die in 1834.

Moore would die in 1852 after a brief lapse into senile dementia.

Edgar Allen Poe, the American poet, and author, is noted as recognizing his favorite song of Moore, “Come Rest in My Bosom”. For three-quarters of a century, more men and women read and loved Moore more than Keats, Shelly, or Wordsworth. Shelly was proud to acknowledge his own inferiority.

Despite this level of recognition, Moore would fall short in being recognized by the cultural leaders in Ireland. His success contrasted the life Edward Bunting was living and his publications were copied and reproduced by other publishers since no copyright laws existed until the late 19th century. Moore was able to capitalize on his airs and Bunting was uncomfortable with them being adjusted to suit his poetry.

At a gathering in Belfast, Bunting was honored and Moore was crushed that he was never mentioned, purposefully, being the possible poet laureate of Ireland.

“Ironically, when the Irish melodies did appear under another imprint -- the airs, of course, were public property-- Bunting, gracious if probably chagrined, said generously that they were “the most beautiful popular songs composed by any lyric poet.”

Moore’s five children would predecease him, three dying at a young age. In 1846 he would write, “The last of our five children is gone and we are left desolate and alone, not a single relative have I now left in the world”, his father deceased in 1825, and his mother in 1830, sister Ellen would die in 1834.

Moore would die in 1852 after a brief lapse into senile dementia.

The theme of love and death appear often in Moore’s works and would play a part in his personality and vision throughout his life

*Thank you great-great grandmother Sarah for the heritage that now rests with me. I regret never having known you, your daughter and your grand daughter; or any other member of the Ruddick family. But don't feel bad because I also never met another Wright.

I did meet a lot of Perrys on my mother's side, but they're all gone now too. That's life for you!

No comments:

Post a Comment