For the past month I have literally lived in my garage with the faint hope of making an end-of-June, 2016, deadline for a yard sale that promises to be the granddaddy of them all. The reason it has taken so long is that I diligently weigh the value of each and every item, often taking long pauses to consider relative merits -- and relish the associated memory.

Deeply engrossed in the "do I or don't I" undertaking, it has not been unheard of for me to fall asleep as my mind drifts through days of yore -- my youth, marriage, two daughters, grandchildren, special occasions, work I've done, the lives and deaths of immediate family members. Tonight, for instance, I was in the garage and sitting in an old arm chair that once belonged to my late wife's parents. As I contemplated all the work that was still ahead of me before the target weekend, I dozed off and woke up an hour later with a stiff neck and nothing accomplished...Story of my life!

One thing I did accomplish tonight, however, was the decision not to dispense with a cup and saucer that I purchased (along with several other incidental items) at the time of the closing of the fabled post war Lord Simcoe Hotel in Toronto in 1979. I have a thing for old hotels and have always prized the Lord Simcoe cup and saucer, with its LS logo, as a memento of an era past. I call it my "Sarah Siddons cup and saucer" because it is a souvenir tribute in high grade china to "the incomparable English actress" of the 18th century. The inscription on the saucer further reads: "Sarah Siddons...fused stage and society, frequented the Pump Room and hobnobbed with aristocracy while playing stock in Bath."

The "Duraline" cup and saucer is super vitrified and made for the Grindley Hotelware Co. in England. Just because I can, I'll be drinking my coffee out of it in the morning, just as I did in the Lord Simcoe's Pump Room on numerous occasions some 38 years ago. The hotel actually had three restaurants -- The Pump Room, The Captain’s Table and The Country Fare -- all decorated in historical styles. The luxurious Pump Room was reportedly inspired by its 1795 neoclassical namesake in Bath, England; accordingly, waiters wore long red tailcoats and served prime rib skewered on swords.

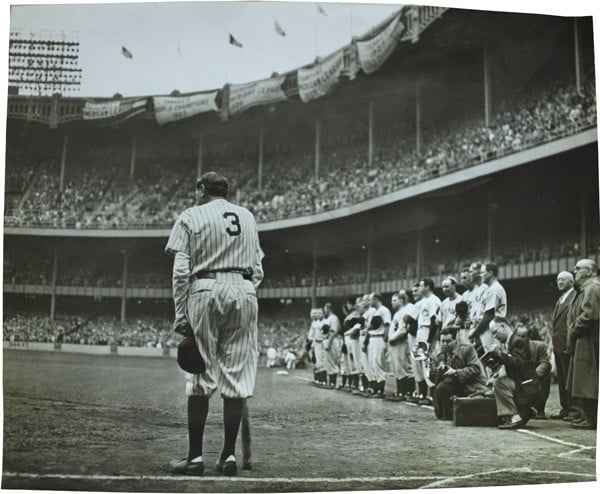

|

| Sarah Siddons as painted by Thomas Gainsborough. |

In case anyone has further interest, Sarah Siddons (1755-1831) was the renowned tragic actress who dominated British theater during the late Georgian era. She was most famous for her portrayal of the Shakespearean character: Lady Macbeth, a role she made her own. The Sarah Siddons Society continues to present the Sarah Siddons Award in Chicago every year to a prominent actress.

Sarah was born July 5, 1755 into the family of strolling actors Roger Kemble and Sarah Ward Kemble. She began to perform with her parents rather early, the first documented stage appearance of Sarah Kemble, aged 11, is dated December 22, 1766; she played Ariel in the Tempest with her father’s company at Coventry. Four of Sarah’s siblings -- out of 11 total -- were to become actors; besides Sarah the most famous was John Philip Kemble (1757-1823), but also Stephen Kemble (1758-1822), Charles Kemble (1775-1854) and Elizabeth Whitlock (1761-1836).

In 1767 William Siddons, a handsome 22-year-old actor, was accepted into the Kemble company. To stop the relationship between their daughter and William Siddons, the Kembles sent Sarah away to serve as maid to Lady Mary Greatheed. However, the feelings between the two young people were stronger than her parents realized and in 1773, aged 19, Sarah married William Siddons and returned to the stage as Mrs Siddons, continuing to perform with her father’s company.

In 1775 the famous Garrick, then manager of Drury Lane Theatre in London, invited her to perform with his company, but she failed to produce a favorable impression on the public and was dismissed within several months. She spent the next two years working with various touring companies, until 1778, when she was engaged at the Theatre Royal in Bath. She was an astonishing success with the Bath public (as referenced on the cup saucer inscription) and in 1782 the new manager of Drury Lane Theatre, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, invited her back to London.

She appeared in the title role of the tragedy Isabella. Her performance moved the public to tears and critics to enthusiastic praise. A string of very successful roles followed. The actress was even popular with the royal couple, George III and Queen Charlotte, known for their antipathy to theater. They appointed Mrs. Siddons “Reader in English” to the royal children.

In May 1784, Reynolds exhibited Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse at the Royal Academy. The picture was instantly proclaimed a masterpiece, increasing the popularity of both its creator and the model. The actress spent that summer touring Scotland and Ireland. Scotland greeted the actress enthusiastically, but in Ireland, she refused to participate in a benefit performance and the irritated Dublin public assaulted her with apples and potatoes during the show. The reason for the refusal was not the selfishness of the actress, but exhaustion and poor health – her constant pregnancies, childbirth, miscarriages, anxiety to secure the future of her growing family and financial problems could not but tell on her health.

Unfortunately, rumors of her “selfishness” reached London and she was booed on her opening night as Mrs. Beverley in Edward Moore’s tragedy The Gamester. The uproar lasted for 40 minutes, during which the actress fainted. After recovering she addressed the public with explanations and apologies. Tempted to abandon her profession by this incident, she decided to continue for her children’s sake.

Siddons’s brilliant career lasted till 1812, when she made her official farewell performance at Covent Garden in her signature role of Lady Macbeth. Impatient with retirement, Siddons made several benefit appearances, among them 10 performances in Edinburgh for the benefit of her son Henry’s widow and their children after his death in 1815.

Sarah Siddons died on May 31, 1831, aged seventy-six, in her house on Upper Baker Street, London. She outlived five of her seven children, her husband, her brother John Philip Kemble, and the painters Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Lawrence (1768-1830) on whose remarkable portraits she appears. She was buried at St. Mary’s, Paddington, on 15 June. Five thousand people attended her funeral.

My coffee in the morning will also serve as a toast to Sarah. Haven't decided yet where I'm once again going to display the cup and saucer in my house. I'm just glad that I decided to save it from the cut. I'll probably leave it on the kitchen table for now.

In May 1784, Reynolds exhibited Sarah Siddons as the Tragic Muse at the Royal Academy. The picture was instantly proclaimed a masterpiece, increasing the popularity of both its creator and the model. The actress spent that summer touring Scotland and Ireland. Scotland greeted the actress enthusiastically, but in Ireland, she refused to participate in a benefit performance and the irritated Dublin public assaulted her with apples and potatoes during the show. The reason for the refusal was not the selfishness of the actress, but exhaustion and poor health – her constant pregnancies, childbirth, miscarriages, anxiety to secure the future of her growing family and financial problems could not but tell on her health.

Unfortunately, rumors of her “selfishness” reached London and she was booed on her opening night as Mrs. Beverley in Edward Moore’s tragedy The Gamester. The uproar lasted for 40 minutes, during which the actress fainted. After recovering she addressed the public with explanations and apologies. Tempted to abandon her profession by this incident, she decided to continue for her children’s sake.

Siddons’s brilliant career lasted till 1812, when she made her official farewell performance at Covent Garden in her signature role of Lady Macbeth. Impatient with retirement, Siddons made several benefit appearances, among them 10 performances in Edinburgh for the benefit of her son Henry’s widow and their children after his death in 1815.

Sarah Siddons died on May 31, 1831, aged seventy-six, in her house on Upper Baker Street, London. She outlived five of her seven children, her husband, her brother John Philip Kemble, and the painters Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Lawrence (1768-1830) on whose remarkable portraits she appears. She was buried at St. Mary’s, Paddington, on 15 June. Five thousand people attended her funeral.

My coffee in the morning will also serve as a toast to Sarah. Haven't decided yet where I'm once again going to display the cup and saucer in my house. I'm just glad that I decided to save it from the cut. I'll probably leave it on the kitchen table for now.